In recent years, archaeologists have turned to lasers in order to unearth ancient civilizations that were previously invisible.

A laser technology known as LiDAR — short for light detection and ranging — uses planes to beam thousands of laser pulses from the sky at the ground below, penetrating through thick, deep forest canopy. That provides researchers with three-dimensional maps underneath the vegetation, revealing human-built structures.

From a Mayan city to complex villages deep in the Brazilian Amazon, here are five previously unknown civilizations that were discovered through state-of-the-art LiDAR technology.

A hidden 2,000-year-old Mayan civilization in northern Guatemala

Using laser pulses, researchers detected a 2,000-year-old Mayan civilization in northern Guatemala with nearly 1,000 archaeological sites.

From their topographical maps of the area, they determined that the civilization consisted of more than 417 cities, towns, and villages spread across 650 square miles.

The settlement had dozens of ball courts and 110 combined miles of navigable causeways that allowed ancient Mayans to travel.

The findings were published in the journal Ancient Mesoamerica in December.

Nearly 500 long-lost Maya and Olmec ceremonial sites in Mexico

In a study published in October 2021, researchers uncovered 478 Mesoamerican sites they estimated were between 2,000 and 3,000 years old.

The sites are spread across a 32,800-square-mile area in the Mexican states of Tabasco and Veracruz, where the Olmec and Maya civilizations flourished.

The finding helps archeologists connect the Olmec and Maya cultures.

“It was unthinkable to study an area this large until a few years ago,” Takeshi Inomata, an anthropologist with the University of Arizona who co-authored the study, said in a press release at the time, adding that LiDAR technology is “transforming archaeology.”

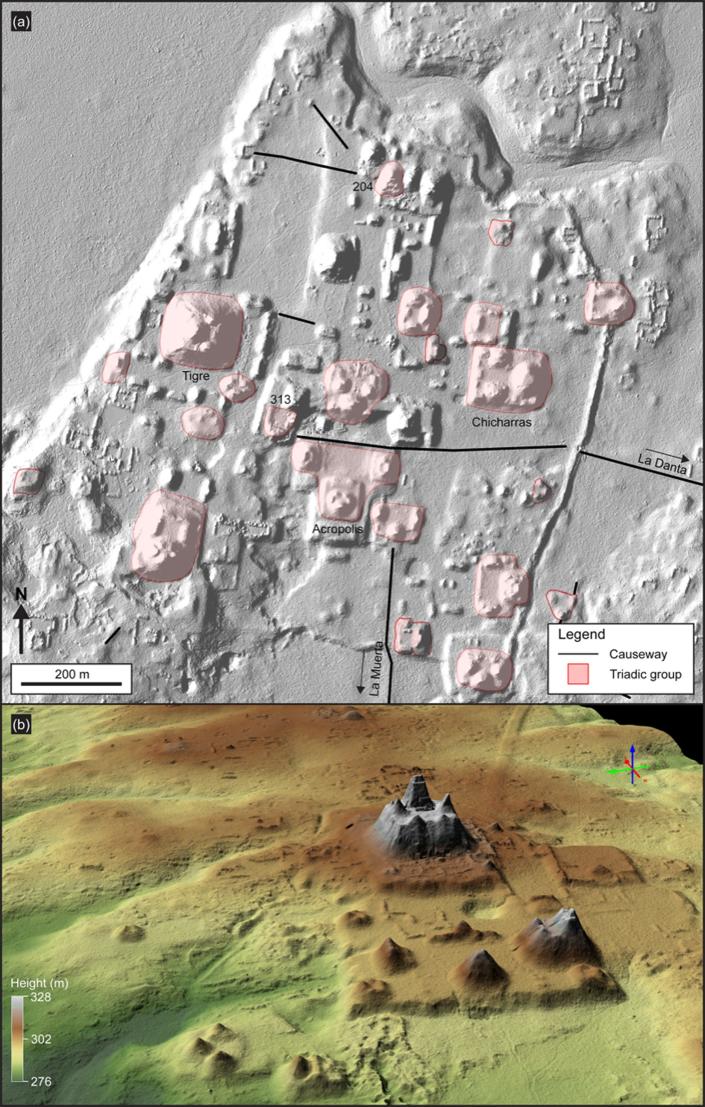

61,000 previously unknown structures hidden under the dense Guatemalan jungle

In 2018, researchers used laser technology to map Petén, Guatemala, where the Mayans once lived.

They discovered 61,480 long-lost roads, foundations for houses, military fortifications, and elevated causeways. They all date back to 650 and 800 CE, in the Mayan Late Classic Period.

“Seen as a whole, terraces and irrigation channels, reservoirs, fortifications and causeways reveal an astonishing amount of land modification done by the Maya over their entire landscape on a scale previously unimaginable,” Francisco Estrada-Belli, an anthropologist at Tulane University and co-author of the study, said in a press release.

81 earthworks, including fortified villages and roads, deep in the Amazon rainforest

An aerial photo of an earthwork mound constructed over 500 years ago in the Amazon.Courtesy of Jonas Gregorio de Souza/ University of Exeter

In Brazil’s Mato Grasso region, archaeologists used LiDAR to find evidence of 24 sites with 81 earthworks, which included interconnected roads and fortified villages built on mounds.

They believe the structures may have supported a complex civilization containing a population of up to 1 million people between the years 1250 and 1500, Insider previously reported.

Some of the geoglyphs, as archaeologists call the sites carved into the Earth, were up to 1,300 feet across.

There may be hundreds more sites hidden in the jungle in a “continuous string of settlements,” Jonas Gregorio de Souza, the paper’s lead author, told the Wall Street Journal in 2018.

“It seems that it was a mosaic of cultures.”

An overgrown ancient civilization buried in the Bolivian Amazon

In what is now Bolivia, LiDAR revealed the hidden ruins of 26 Indigenous settlement sites, nine of which were new discoveries, that thrived in the Amazon rainforest more than 600 years ago.

The settlements were from the Casarabe culture, which occupied an area of approximately 1,700 square miles between 500 and 1,400 CE.

They also unearthed stepped platforms and conical pyramids up to 72 feet tall.

“Our results put to rest arguments that western Amazonia was sparsely populated in pre-Hispanic times,” researchers wrote in the journal Nature.

Source: Business Insider