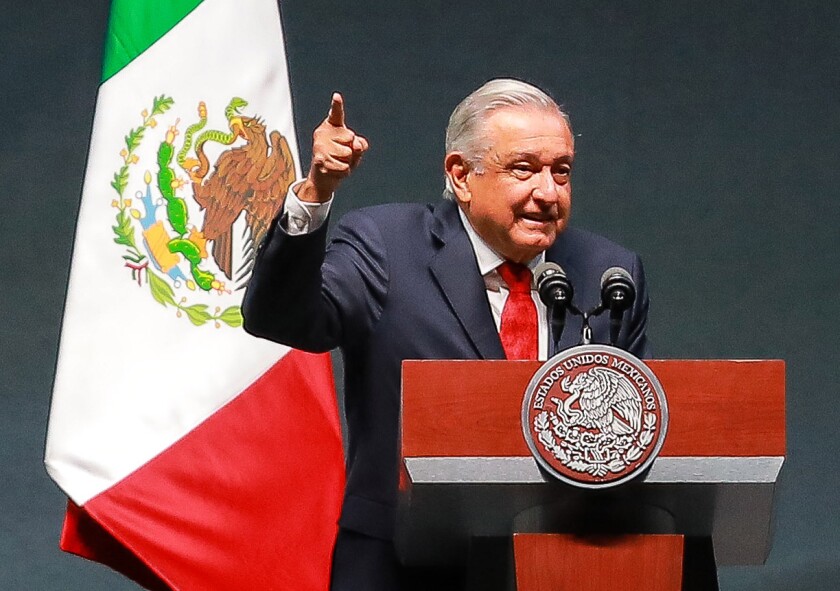

Standing before hundreds of thousands of supporters in Mexico City’s Zócalo, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador saved his most striking comment for the end of his speech.

He urged the Mexicans gathered in the Zócalo to participate in an April referendum to decide if they want to expel him from the office more than two years in advance.

“No ‘I was elected for six years and I can do whatever I want,'” López Obrador said at Wednesday’s rally to mark his midterm. “If one who governs is not up to the task and does not obey the people, revoke his mandate and go!”

The 68-year-old president probably thinks he has nothing to worry about.

Recent polls show that around two-thirds of the public approves of his performance since he took office in 2018 on a platform that promised a radical transformation of Mexican society to combat corruption and inequality, as well as reverse free-market economic policies.

Families and music bands heading to the Zócalo passed merchants selling gray-haired López Obrador dolls and posters with the hashtag #QueSigaAMLO, referring to the president by his initials. Many said they see a referendum, authorized by a 2019 constitutional reform led by the president, as proof of his honest character compared to decades of leaders accused of corruption.

“AMLO is the first president who dares to test himself before the people,” said Debanhi Andrea García, 22, who drove 14 hours from the state of Nuevo León with her boyfriend. “We support him because he is like that.”

Mexicans have until December 25 to sign a petition to support the referendum, which can only advance with the signatures of at least 3% of eligible voters, among other caveats.

So far, the initiative has received more than 703,000 signatures from Mexicans who have valid voter credentials, or 25% of the total required, according to the National Electoral Institute, an independent body that oversees the process (that count includes signatures that will be discarded because are duplicates or have other irregularities).

Officially called “mandate revocation,” the measure follows other efforts by the president to increase citizen participation in public policy. López Obrador has also backed referendums to decide whether former Mexican presidents should be prosecuted for alleged crimes, on the construction of a new airport near Mexico City and on the development of a tourist train line that would cross the Yucatan Peninsula.

“He sees his power in terms of people actively reiterating their support,” said Francisco González, a professor of Latin American politics at Johns Hopkins University. “He wants it to be officially confirmed to give him that consolation of being the popular leader who is doing the right thing for Mexico.”

Since taking office, López Obrador has also expanded social welfare programs while introducing strong austerity measures. He has stopped renewable energy projects, promoted a constitutional reform to increase the country’s control over the electricity market, and has given more power to the military, putting them in charge of projects such as the tourist train.

His critics stress that he has not done enough to reduce the high levels of homicides, including many murders of women, as well as attacks on journalists and public officials. Dozens of candidates across the country were assassinated before midterm elections for governors, legislatures, and municipal presidencies last spring.

Critics are also concerned about López Obrador’s attacks on democratic agencies that could control his power, in particular the National Electoral Institute. He has repeatedly disparaged the independent agency, which sanctioned him last May for making statements at least 29 press conferences that he said could be seen as government propaganda that could influence the midterm elections. In Mexico, such statements by public officials are generally prohibited during election season.

But the president’s vision for transformative change continues to resonate with many voters who view him as a father figure. López Obrador is in constant dialogue with his electorate, holding press conferences every morning that lasts for hours.

“The figure that he has built of an honest man, an honorable man, an incorruptible man, that helps him in a society that is used to seeing terribly corrupt politicians,” explained René Torres-Ruiz, a political scientist at the Ibero-American University in the City of Mexico.

Even if enough signatures are gathered, obstacles to a referendum remain. Members of the National Electoral Institute have indicated that the agency does not have the budget to carry out the vote and at least 40% of eligible voters must participate for the referendum to be binding. The referendum on former presidents last August was well below 40% of the vote.

Stephanie Brewer, director for Mexico and Migrant Rights at the Washington Office for Latin American Affairs, pointed out that winning a referendum would increase López Obrador’s perception that he can freely advance his agenda.

“What he wants is to get out of the vote, assuming there is one, politically strengthened with this renewed and expanded popular mandate,” he emphasized.

Opposition parties have accused the president’s supporters of twisting the declared purpose of the referendum and turning it into a tool to advance López Obrador’s agenda. The 2019 reform called for a referendum to “revoke” the mandate of a president instead of “ratifying it” and a complaint before the National Electoral Institute, by the National Action Party, made reference to how volunteers have registered voters together with posters who advertise the referendum as a means of promoting the president, rather than removing him from office.

Luis Cházaro, a congressman from the Party of the Democratic Revolution, told the Times that the referendum “has become a tool for promoting the party.” He does not plan to participate.

In Coyoacán, a neighborhood in Mexico City known for Frida Kahlo’s house, volunteers collected signatures in a plaza in front of the president’s signs that said “AMLO continue,” last Sunday.

Ariana García, a 24-year-old volunteer, indicated that she uses the term “ratification” for people who feel they support the president and “revocation” for those who believe they oppose him.

“People tell you, ‘but I don’t want my president to leave,’ then we tell them, ‘It’s okay, in that case, you can ratify your support for the president,” he explained.

Roberto García, a systems engineer in Mexico City, mentioned that he would vote against the president, being uncomfortable because the federal government recently issued a decree that requires federal agencies to automatically approve infrastructure projects deemed to be of interest to the public. or national security. He also sees the referendum as “a kind of manipulation”, suspicious of why the president has contradicted the National Electoral Institute, arguing that he has sufficient funds to carry out a vote for which he himself has fought.

María de los Ángeles Resendiz, a grandmother of 10 from the state of Mexico, will support López Obrador without hesitation.

Resendiz, 62, watches the president’s press conferences at 7 a.m. every day with her husband as he cooks breakfast and does the dishes. If you need to skip one, you’ll find it later on YouTube. Also, listen to the summaries in case you missed something.

Before López Obrador took office, Resendiz tried to stay as far away from politics as possible. She was disillusioned as a child after the 1968 Tlatelolco massacre when soldiers killed up to 300 people at a student protest in Mexico City.

He called López Obrador a “simple” man who has earned his trust with his anti-corruption platform. She enthusiastically described how her government has set aside money for job training for young people and expanded welfare payments to the elderly.

“It has given us our dignity back,” he said. “I am proud to say that I am Mexican and that he is my president.”

Source: latimes.com/espanol